S2E5: Aortic Dissection | POCUS in AD | The Aortic Dissection Charitable Trust

After a well deserved break in January, our team are back and have outdone themselves with our first episode of 2022.

Firstly discussing the case we have Leah, Orla and Timbs.

Our Adult In The Room Dr John Cronin, Consultant in Emergency Medicine at St. Vincent’s University Hospital, will be reviewing our work and delves into the challenge of differentiating chest pain.

Callum and Timbs talk all things ultrasound in the Echo Chamber

Finally, Orla is joined by Catherine Fowler of the Aortic Dissection Charitable Trust to talk about the amazing, important work they do.

Right… let’s get to it!

Aortic Dissection

Back to the Basics

An aortic dissection generally occurs when a false lumen is formed in the intima of the aorta, which blood then enters. As the tissue separates, the influx of blood causes weakening of the media and ultimately, a dissection.

Why is it considered an Emergency?

Notably, AD has an increasing mortality of approximately 1-2% per hour after onset. If left untreated, mortality can be up to 50% in the first 48hours [1].

The Great Mimicker

A few things can give you the overall spectrum of “aortic syndrome”. These include an intramural haematoma, aneurysm formation, penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer and AD. Aortic dissection is an uncommon presentation to our emergency departments and as such may be missed [1].

Who’s Affected?

Risk Factors

The most common risk factor in the The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) series was hypertension (76.6%). Other risk factors include cardiac structural abnormalities, previous cardiothoracic surgery or PCI, infections, arteritis and the use of cocaine as these all cause stress on the aortic wall.

Genetic conditions such as Marfan’s, Ehlers-Danlos and Turner’s syndrome can all predispose to aortic aneurysms and should be considered in younger patients presenting with symptoms.

A family history of AD is also important to elicit.

Demographics

AD commonly affects males (67%) and between the 40 - 70 years of age [2]. Females tend to be older and have a delayed presentation and diagnosis.

IRAD reported that younger (<40 years) patients are more likely to have a history of Marfan’s or Bicuspid Aortic Valves compared to elderly (>70 years) patients who were more likely to have HTN, atherosclerosis or prior aortic aneurysm [2].

Much like females, older patients had a delayed presentation and diagnosis.

Signs and symptoms

Acute aortic dissection has a variety of presentations, and thus, we should always try and consider it. Stereotypically, the pain is considered a maximal-at-onset, “tearing” or “sharp” chest pain, that radiates down the back or migrates.

Retrosternal chest pain is usually seen in an anterior dissection, while interscapular pain may be described in dissection of the descending aorta.

A proportion of patients will present with painless (6.3%) AD [2]. These patients were more likely to present with syncope, stroke and heart failure and experienced delayed diagnosis [2]. This highlights why AD can be a challenging diagnosis for clinicians.

Investigations

ECG

As with most patients with chest pain, it’s important to obtain an ECG but in most cases, this will be normal. However, evidence of acute MI may occur in end-organ complications or signs of pericarditis. In the IRAD study, 5% of patients presented with MI on ECG, 15% with signs of ischaemia and 42% with non-specific ST and T waves changes.

Troponin

Similarly, the troponin tends to be raised when there is myocardial ischaemia. However it is not discriminatory for AD and can lead clinicians into a rabbit hole to treat ACS. Ultimately, the last thing a patient with AD needs is anticoagulation which would be the mainstay of treatment if positive troponin is seen in the setting of chest pain.

D-Dimer

Ah, our beloved D dimer. Numerous papers have been published on whether or not D-dimers should be used in the diagnosis of aortic dissection. As with many things, the evidence is overall unclear and the methodology of some of the papers tends to have bias and no RCT has yet been conducted.

Bottom-line is that if you have a lower pre-test probability, then you’re less likely to miss an AD and there may be a role for running a D-dimer. However, if you’re in anyway suspecting an aortic dissection (which you probably are if you’re considering this), it’s not worth it and won’t change the need for urgent CT and subsequent management. Waiting for a D-dimer may only delay diagnosis further.

Chest X-ray

In the assessment of patients with suspected AD, the CXR has some useful features. Which include:

widened mediastinum (>8cm)

Pleural effusion

Deviation of the oesophagus

Deviation of the trachea to the right

Depression of the left mainstem bronchus

However, 20% of AD patients can present with no CXR findings. This is important as dissections occurring just below the diaphragm or non dilated aorta would not present with any CXR features.

In reality, if you’ve a high clinical suspicion for dissection, this patient would ideally be going straight to CT without CXR. Consider it the “tension pneumothorax” of the vascular world… you shouldn’t see it on a CXR.

ECHO

The use of transoesophageal ECHO (TEE) has declined over time with the advent of CT angiography [2]. However, its utility is patients who are hemodynamically unstable for CT and intraoperatively for assessment. The availability of TEE in our EDs in Ireland for AD patients is not that common. However, if waiting for transfer to CT, throwing on your bedside echo is definitely a good option and can give us key clues about what might be going on.

CTA

CT angiography aorta is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of AD. Features on the CT that confirm the diagnosis are as follows:

Intimal dissection flap

Double lumen

Aortic dilation and hematoma

Regions of malperfusion

Contrast leak indicates aortic rupture

CTA is important not good only for diagnosis but surgical planning and assessment for complications.

Classification

So we've diagnosed an aortic dissection, what now? Classification of course! This is carried out with the Stanford (more commonly used) or DeBakey systems.

Stanford

Stanford Type A dissection involves the ascending aorta and can extend further. They account for about 60% of aortic dissections. Importantly, these patients usually require surgery under cardiothoracics. If the dissection extends into the pericardial sac, this can cause cardiac tamponade.

Type B is when the descending aorta is affected distal to the level of the left subclavian artery. These are usually managed medically with tight blood pressure control.

DeBakey

The DeBakey Classification has three divisions:

Type I involves the ascending and descending aorta.

Type II involves the ascending aorta only.

Type III is isolated to the descending aorta.

Management in the ED

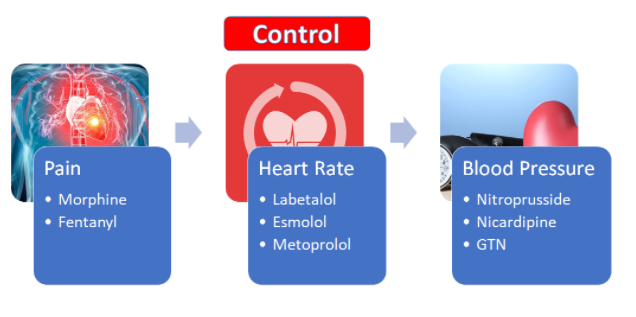

Good analgesia is important. Paracetamol won’t be touching the pain of a dissection so start low and go slow with some morphine and titrating to patient response and vital signs.

Blood pressure is the mainstay of aortic dissection management within the Emergency Department while waiting for definitive management. Labetalol is usually the one to start with at 0.25mg/kg as a bolus over 20 minutes and then further boluses as required. Your aim is to keep the systolic blood pressure less than 120mmHg. After your initial dose has gone in, it would be good to get an arterial line in, in order to offer us some better insight into that blood pressure control.

Importantly, if you’re administrating an alpha or beta blocker, you must also use a nitrate. Blockers used in isolation may cause peripheral vasoconstriction. GTN is a good place to start at 2-10mg/hour.

Definitive Management

Type A dissections require surgical treatment. Operative mortality has dropped over recent years from 25% to 18% due to recent advances. Note: immediate surgical repair is contraindicated if concurrent or progressing stroke. Stabilising these patients for transfer are crucial.

Type B dissections are usually treated medically with tight blood pressure control and analgesia. Surgical risks are often higher than in type A. However, if they are experiencing complications of their dissection, they may be considered for surgical intervention.

You can download this printable infographic here!

The Aortic Dissection Charitable Trust

We are incredibly fortunate to be joined this month by the amazing Catherine Fowler, trustee of the The Aortic Dissection Charitable Trust.

Catherine shared her incredible story with us and also gave us an insight into the crucial perspective of the patient and patient’s family. The ADCT do important work around raising awareness amongst the wider public but also amongst healthcare professionals.

Keep an eye out for the Global Aortic Dissection Awareness Week starting September 18th.

Not only that, but around this time, the Trust are liaising with RCEM and IAEM to organise an important educational awareness day for trainees and starting to implement a treatment pathway that will be available across pre-hospital medicine, Emergency physicians, radiology and our surgical colleagues. The week will also include an AD Patient Day where we will hear the stories of patients and patients’ families to understand more about AD and management.

Stay tuned on the ADCT website and we will be sure to post the details on our social media!

Page Last Updated:

14/02/2022