S1E3: Upper GI Bleed | Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy Airway Decontamination (SALAD) | Tips for New EM Staff

Welcome back everyone to another episode of TheCase.Report!

If you’re a denizen of med twitter like us, then your world will have been rocked by the HALT-IT trial results too. But it’s important to remember that there’s more to upper GI bleeding than TXA!

With that in mind, Orla, Timbs and Mohammed will tackle a case of an upper GI bleed. Think they’re up to the challenge? Our AITR Dr. Trish Lucey will check their work!

For our second segment, Timbs sat down with Dr. Nicolas Lim to chat about Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy Airway Decontamination (SALAD) – and I apologize in advance for all the salad jokes…

For our last segment today, we’ve got a changeover special! Orla’s kindly come back with some tips for anyone new to EM, to help you get started on the right track.

Right, let’s get to it!

Introduction

Always in the Emergency Department the question is stable or unstable? But in the case of GI bleeds, three synchronous questions have to be asked - stable or unstable? Upper or lower bleed? Variceal or non-variceal? These questions will lead to different management of patients so must be asked at the start of each case.

The Stats

Upper gastrointestinal bleed (UGIB) is a common presentation to the emergency department (ED) accounting for 5% of presentations per year and up to 3% of hospital admissions [1].

Despite advances in endoscopic therapy, UGIB still carries a mortality between 2% to 15% in severe cases [2].

Variceal bleeding has a very high early mortality rate of up to 30% and up to 47%-74% of patients will have recurrent bleeding [3]

The aim in the management of these patients is risk assessment using the Glasgow Blatchford score (GBS), resuscitation, endoscopy within 24hours for admitted stable patients or immediately for hemodynamically unstable patients. These are based on the recommendations of both National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines for patient presenting with UGIB.

Causes

Clinical Presentation

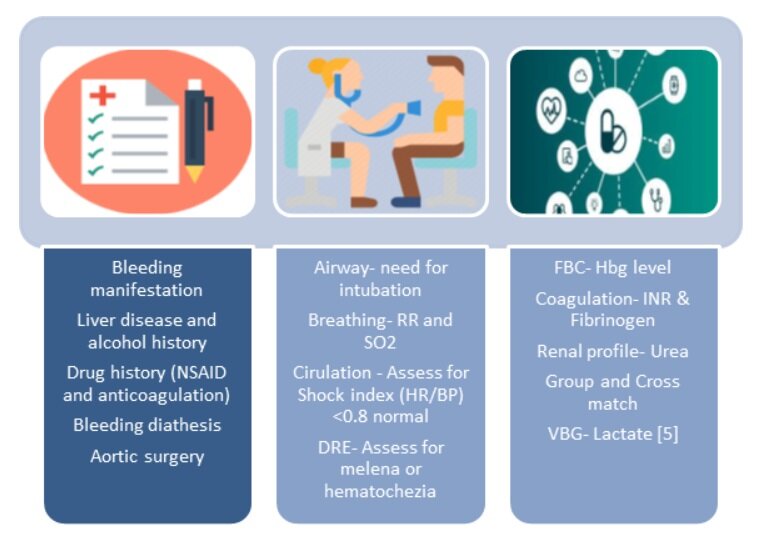

The clinical presentation or manifestations of UGIB are listed in the above figure. Melena has a reported likelihood ratio of 5.9 for history and 25 for examination [4]. However, be cautious as certain foods can imitate malena such as iron, bismutth and black foods (licorice). If the UGIB is acute, there may not be time for the blood to have transited the whole bowel. Hematemesis/Coffee ground vomiting is a commonly reported manifestation of UGIB but consider other sources of bleeding such as posterior epistaxis. In shocked or hemodynamically unstable patients it's always good to have UGIB as a differential diagnosis particularly in the elderly. Heamatochezia is reported as fresh blood per rectum which most often represents lower GI bleeding, however can be present with brisk bleeding from the upper GI tract (proximal to the ligament of Treitz). Other related pathologies include GI bleeding from an ischemic bowel, which although is a GI bleed, its treatment is drastically different. This must be considered in patients with abdominal pain, high lactate and/or pro-thrombotic conditions. An aorto-enteric fistula is another cause that can cause life threatening haemorrhage within minutes and must be suspected if the patient has a history of AAA repair or other aorto-vascular surgery.

Clinical Assessment

History

The patient’s history will enable you to answer those all important questions we asked above - is this an upper or lower GI bleed, and if it is upper, is it variceal or non-variceal? Ask specifically regarding alcohol history and regular medications. Don’t miss a bleeding diathesis or previous aortic surgery. In the case above there are red flags for both variceal and PUD bleeding.

Risk Assessment

The Glasgow Blatchford score (GBS), the pre-endoscopic or “admission” Rockall score, and the AIMS65 score are the most widely utilised risk stratification scores for patients presenting with UGIB.The Rockall score and AIM65 were developed to predict mortality while the GBS predicts both clinical intervention and mortality. The GBS has been compared to the Rockall score and AIM65 in various studies which has shown that the GBS seems to be superior at predicting a combined endpoint of intervention or death [6].

[6] AJ Stanley et al.Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ 2019

[6]AJ Stanley et al.Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ 2019

Glasgow-Blatchford Score (GBS) [7]

Produced in 2000

Clinical score ranging from 0-23

Superior at the prediction of composite endpoint of “need for intervention or death”, also better at predicting need for endoscopic intervention

AIMS65 Score [8]

Produced in 2011

Score ranging from 0-5

Easier to calculate than GBS

Better at predicting mortality

Rockall Score [9]

Produced in 1996

Range from 0 - 7 for pre-endoscopy Rockall score

0 - 11 for full Rockall score

Full Rock all score incorporates endoscopy findings, therefore pre-endoscopy Rockall score produced for utilisation in ED.

Better at predicting mortality

ESGE recommends the use of the Glasgow-Blatchford Score (GBS) for pre endoscopy risk stratification. Low risk patients (GBS <1) do not require admission or immediate endoscopy. These patients can be discharged with advice regarding the risk of recurrence and planned for outpatients endoscopy [10]. Patients presenting with a GBS<1 or AIMS-65 of 0 could be safely discharged from the ED for outpatient management, thereby avoiding admission in 19-24% of patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding [6].

Fecal Occult Blood Test

If someone is having active haematemesis there is no need to do an FOB test, it will not add any clinical benefit. It can be useful in patients who clinically it is unsure whether or not a GI bleed is occurring, however beware the false positives (colchicine, iodine, boric acid, red meat) and false negatives (vitamin C).

Resuscitation

The immediate priority when managing an unstable UGIB is adequate resuscitation with bloods products (massive transfusion protocol early) and reversing any coagulopathies presents. The next step after adequate resuscitation is plugging the hole (bleed), hence transfer for endoscopy management is vital.

Airway

If drowsy (low GCS) and vomiting, intubation must be considered, however studies have shown there to be increased risk of unforeseen cardiopulmonary events and pneumonia in patients who have been prophylactically intubated [11, 12]. Beware induction agents that cause hypotension and vasodilation, and intubating under conditions of high risk of aspiration and poor visualisation. If possible aggressively resuscitate so as to negate the need for intubation.

Breathing

Start on O2 via nasal prongs

Circulation

IV access x 2 (<18G), central position.

Intravenous fluids: RCT in patients with hemorrhagic shock as a result of trauma suggest that a more restrictive fluid resuscitation may be better (or not worse) than more intensive fluid resuscitation. There are no studies looking at fluid resuscitation in UGIB [13]. However, from extrapolation of the literature it is best to avoid excessive crystalloid resuscitation and recommend giving a minimum amount of fluid to maintain MAP > 60 mm Hg. Variceal haemorrhage in particular can worsen with over resuscitation as it increases portal venous pressure, therefore restrictive fluid regimes should be instigated.

RCC Transfusion: Blood transfusion is not without risk, and also increases portal pressures in variceal bleeds, so should be performed judiciously. Multiple studies have failed to show a benefit of higher transfusion thresholds, and a restrictive approach has been shown to be beneficial, as such transfusion should be withheld until a Hb of 7-8g/dL[6]. Haemoglobin often lags behind bleeding, so trend it by repeating the haemoglobin in an hour or two. Transfuse if actively bleeding and displaying signs of haemodynamic instability regardless of haemoglobin level. In haemodynamically unstable patients and shock index >1 consider major transfusion protocol. In massive transfusion protocol (MTP) blood products will be provided with a 1:1:1 ratio of PRBC:FFP:platelets. Also consider cryoprecipitate, IV calcium, and a warming blanket.

[14] Helman, A, https://emergencymedicinecases.com/gi-bleed-emergencies-part-1/. 2017.

Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents management: Guidelines around the reversal of anticoagulation in UGIB are less clear and are generally based on expert recommendations. For patients on warfarin with life-threatening bleeding, vitamin K 10mg IV and Octaplex should be given. For less severe bleeds, vitamin K IV may suffice, and in minor bleeds, discontinuing the medication or giving PO vitamin K may be sufficient. For patients with severe bleeding on DOAC’s, reversal agents are available.

Proton Pump Inhibitors: Utility of PPI in management of undifferentiated UGIB was reviewed by REBELEM (Salim Rezaie) looking at 2 main meta-analysis on PPI vs Placebo or H2B and 1 meta-analysis on bolus vs infusion IV PP [15]. The clinical bottom line is that IV PPI doesn’t improve mortality but reduces the rebleeding rate and need for surgical intervention. For IV bolus PPI vs Bolus, then infusion, there was no significant difference in clinical oriented outcomes [15]. However, the ESGE recommends initiating high dose intravenous proton pump inhibitors (PPI), intravenous bolus followed by continuous infusion (80mg then 8mg/hour), in patients presenting with acute UGIB awaiting upper endoscopy [10]. But this should not delay urgent endoscopy.

Variceal UGIB: Stigmata of liver disease increases the likelihood of variceal UGIB as the etiology when an assessment is performed. Once V-UGIB is suspected modifications to the resuscitation should be made and following considered:

· Vasoactive drugs such as terlipressin and octreotide (a somastatin analogue) reduce the splanchnic blood flow and portal venous pressure. A Cochrane review and meta-analysis showed that octreotide reduces bleeding and transfusion requirements but has no effect on mortality [16, 17]. These drugs should be started as soon as variceal bleeding is suspected.

· Prophylactic antibiotics are higher priority in patients presenting with V-UGIB, as it is possible an infection has precipitated the bleeding. A metaanalysis showed significant reduction in all-cause mortality rebleeding events, and hospitalization length [18]. Ceftriaxone is the antibiotic of choice and should be continued for 7 days

Coagulopathies: Patients with chronic liver disease have complicated clotting profiles with altered production of pro and anti thrombotic factors. They are not as previously thought ‘auto-anticoagulated’ despite deranged INRs.They often have reached a haemostatic equilibrium that can be thrown off balance with aggressive use of vitamin K or clotting factors. Measurement of coagulation profiles and fibrinogen are helpful but these patients should be discussed with gastroenterology or haematology on call to guide management.

To give TXA or not to give TXA??!!

HALT-IT - yet another application for our favourite TXA?

Large (12009 patients, 164 hospitals, 15 countries) multi-center, randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled…All the right words! High quality methodology, which was published in advance of patient recruitment…

What we had before: Cochrane review and meta-analysis: 1701 patients, 8 trials; large reduction in mortality shown, however numerous small studies ≠ large RCT, inconsistencies and biases will affect outcomes…

HALT-IT:Methods: Adults with GI bleeding given 1g followed by 3g over 24h or placeboPrimary Outcome: Death from bleeding within 5 days, numerous secondary outcomes

Results: Surprisingly (understatement) no significant difference between groups for primary outcome, however, higher risk of VTE and seizures.

Strengths and weaknesses like any trial, one limitation you’ll likely hear in your tea room would be (if you’ve a few nerds like me in your tea room) that this isn’t the dose we’d typically think of for TXA… But I think this is important for a different reason. While we may have less adverse events at the lower dose, it’s not likely to have a greater effect on rebleeding is it?

And beyond just showing us a specific limitation of TXA, this really highlights the importance of doing high quality research, even when it seems like the answer is obvious! Paddy Power would’ve cleaned up if they were taking bets on the outcome of HALT-IT…

Have a read for yourselves anyway! It’s open access.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30848-5/fulltext

Sengstaken–Blakemore tube(SBT): This is a last ditch intervention to maintain haemostasis or haemorrhage control. This should only be inserted once a patient has been intubated. Excellent resource by Chris Nickson published on LITFL on indication and insertion of SBT (https://litfl.com/sengstaken-blakemore-and-minnesota-tubes/).

Disability: GCS assessment and threat of aspiration as above consider early intubation. SALAD (Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination) trainers to simulate massive UGIB are important to undergo stress inoculation and plan for how to manage the airway of these patients. Great video by Dr James DuCanto (https://vimeo.com/106280641) and article by Justin Morgenstern of First10EM (https://first10em.com/management-of-the-massive-gi-bleed/) on SALAD and managing UGIB patients with copious hematemesis.

Exposure

Monitor patients’ temperature and avoid hypothermia and hyperthermia as this can affect resuscitation efforts and compound coagulopathies.

Endoscopy:

Endoscopy is the definitive treatment for UGIB and the ESGE “recommends early (≤24 hours) upper GI endoscopy. Very early (<12 hours) upper GI endoscopy may be considered in patients with high risk clinical features, namely: hemodynamic instability (tachycardia, hypotension) that persists despite ongoing attempts at volume resuscitation; in-hospital bloody emesis/nasogastric aspirate; or contraindication to the interruption of anticoagulation” [10].

References

1 Bryant RV, Kuo P, Williamson K, et al. Performance of the Glasgow-Blatchford score in predicting clinical outcomes and intervention in hospitalized patients with upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78(4):576-583.

2 Mokhtare M, Bozorgi V, Agah S, et al. Comparison of Glasgow-Blatchford score and full Rockall score systems to predict clinical outcomes in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:337-343. Published 2016 Oct 31.

3 Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922–938.

4 Srygley FD, Gerardo CJ, Tran T, Fisher DA. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed? JAMA 2012;307: 1072-9.

5 Shrestha et al Elevated lactate level predicts intensive care unit admissions, endoscopies and transfusions in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology 2018:11 185–192

6 Adrian J Stanley, Loren Laine. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ 2019;364:l536 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l536.

7 Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. The Lancet. 2000;356(9238):1318-1321.

8 Saltzman JR, Tabak YP, Hyett BH, Sun X, Travis AC, Johannes RS. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2011;74(6):1215-1224.

9 Vreeburg EM, Terwee CB, Snel P, Rauws EA, Bartelsman JF, Meulen JH, Tytgat GN. Validation of the Rockall risk scoring system in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 1999 Mar;44(3):331-5. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.3.331. PMID: 10026316; PMCID: PMC1727413.

10 Gralnek I, Dumonceau J-M, Kuipers E, et al. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47(10):a1-a46.

11 Hayat U, Lee P, Ullah H, Sarvepalli S, Lopez R, Vargo J. Association of prophylactic endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients with upper GI bleeding and cardiopulmonary unplanned events. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86(3):500-509.e1

12 Chaudhuri, D., Bishay, K., Tandon, P., Trivedi, V., James, P.D., Kelly, E.M., Thavorn, K. and Kyeremanteng, K. (2020), Prophylactic endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients with upper gastrointestinal bleed: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JGH Open, 4: 22-28. doi:10.1002/jgh3.12195

13 Bickell WH, Wall MJ Jr, , Pepe PE, et al. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1105-9. 10.1056/ NEJM199410273311701 pmid:7935634.

14 Helman, A, Swaminathan, A, Rezaie, S, Callum, J. GI Bleed Emergencies Part 1. Emergency Medicine Cases. October, 2017. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/gi-bleed-emergencies-part-1/. Accessed [April 2020]

15 Salim Rezaie, "The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly of Proton Pump Inhibitors in UGIB", REBEL EM blog, February 23, 2017. Available at: https://rebelem.com/good-bad-ugly-proton-pump-inhibitors-ugib/.

16 Corley DA, Cello JP, Adkisson W, Ko W, Kerlikowske K. Octreotide for acute esophageal variceal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(4):946-954.

17 Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A. Somatostatin analogues for acute bleeding oesophageal varices. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(3).

18 Chavez-Tapia N, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Tellez-Avila F, et al. Meta-analysis: antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding – an updated Cochrane review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(5):509-518.

Page last updated:

13/07/2020

![[6] AJ Stanley et al.Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ 2019](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5750084a27d4bd2f4b2e1133/1594576230415-CXNL2FFCHS0BCCLH84KE/GBS.jpg)

![[6]AJ Stanley et al.Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ 2019](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5750084a27d4bd2f4b2e1133/1594576313199-AI7F4IRDS0A87L6MDCCH/GBS+auroc.jpg)

![ [14] Helman, A, https://emergencymedicinecases.com/gi-bleed-emergencies-part-1/. 2017.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5750084a27d4bd2f4b2e1133/1594576543946-CCF70I9E4SMYMB74PVFM/mtp.jpg)